Modernists' Brazil

São Paulo, Brasil

12/01/2026 - 31/01/2026

Modernists’ Brazil

Today there is talk of a “modernist tradition”, which would certainly sound like heresy to those who promoted innovation in the arts in 20th century Brazil. A hundred years ago, to be modern was to be averse to “passalism”,

as they said.

It was the perception of the mismatch between the conservatism of cultural production and the transition from an almost exclusively agrarian economy to industrialization that led to the holding of Modern Art Week at the Municipal Theater of São Paulo in 1922. The festival, organized in the manner of futuristic nights, took place under boos. Even in the capital of São Paulo, the cultural environment was still very provincial. Demonstrations that broke with traditional ways of making culture were not tolerated. In most parts of the country, the values of a society traditionally tied to the land and resistant to change prevailed. In this adverse but changing environment, modernism represented a diffuse desire for updating, which found in modern Brazilian art one of

the most expressive achievements.

Lacking local acceptance and seeking to expand knowledge, the first modernists sought out the great European art centers. Paradoxically, it was from Europe that many of them saw the potential of Brazilian cultural diversity. The interest in so-called “primitivism” — triumphant in the arts of the Old World — was the key that encouraged artists like Tarsila to incorporate aspects of Brazilian reality into their work. Our moderns didn’t have to search exotic places for the popular or ethnic content that enchanted Europeans so much. They found in our landscapes and customs the ingredients for the constitution of a visuality of national character

.

Formally, Brazilian art did not absorb the radicalism of the historical avant-garde, not least because the first Brazilian modernists’ greater contact with European art occurred in the interwar period, when the movement for return to order (retour a l’ordre) prescribed a return to figuration as an antidote to the abstractionist tendency. This was the aesthetic link adopted by our first modernism, in other words, modern art in Brazil remained faithful to figuration, initially with expressionist and cubist accents and, later, with

surrealist touches.

The persistence of figurative representation lasted, among us, until the 1950s, driven by a mission: to serve the constitution of the Brazilian visual identity. The ideology of Brazilianism conditioned early modernism, imposing barriers to the deepening of purely formal issues. Nothing strange. This slow maturation of modern art in Brazil went hand in hand with the country’s slow process of economic and social development

.

Cultural modernity would rise to a new level in 1931, when modern works were admitted, for the first time, to the classrooms of the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro. Because it confronted the aesthetic established in the most traditional art institution in Brazil, that year’s Salon was called “Revolutionary”. Despite the crisis brought about by the event, modernism would come to take hold in that decade, becoming established as a national expression in the 1940s, thanks to official orders to Portinari

.

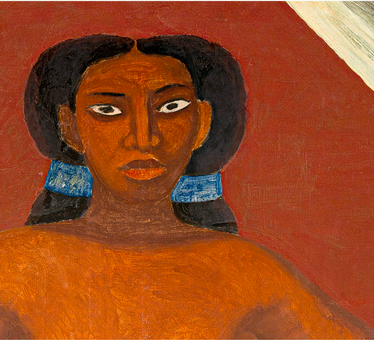

It is undeniable that Tarsila, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Rego Monteiro, Brecheret, Portinari, Guignard constituted an iconographic corpus identified with Brazil. More than that, modernism added updated views of our sociocultural reality to the national imaginary. In other words, when we think of Brazilian women, the sensuality of the brunettes painted by Di Cavalcanti comes to mind; the story of the conquest of our territory takes place at the Monument to the Flags, by Brecheret; our myths are those of Tarsila; our beaches are those of Pancetti; and the popular festivals have their best expression in the color of the

little flags of Volpi.

This exhibition presents striking examples of this visuality. Performed by artists of diverse personalities and backgrounds, this representative language would reach the 1940s, showing signs of exhaustion. That’s when we saw the slow and steady rise of Volpi, represented here by a magnificent set of works. The Italian immigrant, who began painting the walls of the São Paulo bourgeoisie’s houses, was surprised to move from an unpretentious figuration to his own language, marked by the geometrization of elements of houses and popular life. In 1944, the painter married Benedita da Conceição, nicknamed Judite, whose portrait constitutes the most important piece in this exhibition: she appears naked between curtains and, with open arms, seems to present the paintings around her. The pinks, blues, and faded greens of Volpi’s paintings flood the room with light. And this is justified: his painting inaugurated a new era in modern Brazilian art

.

Maria Alice Milliet

November 2025